The Great Salt Lake

Season 4 Episode 6 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Delve into the captivating tale of the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere.

Delve into the tale of the Great Salt Lake which is an integral part of the Salt Lake Valley's culture and identity. Learn of the lake's ecosystem through the world of brine shrimp. Discover how the Great Salt Lake Institute's team of scientists and educators are investigating whether the lake can survive. And experience the poetry of Nan Seymour, whose words advocate for the lake's protection.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

This Is Utah is a local public television program presented by PBS Utah

Funding for This Is Utah is provided by the Willard L. Eccles Foundation and the Lawrence T. & Janet T. Dee Foundation, and the contributing members of PBS Utah.

The Great Salt Lake

Season 4 Episode 6 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Delve into the tale of the Great Salt Lake which is an integral part of the Salt Lake Valley's culture and identity. Learn of the lake's ecosystem through the world of brine shrimp. Discover how the Great Salt Lake Institute's team of scientists and educators are investigating whether the lake can survive. And experience the poetry of Nan Seymour, whose words advocate for the lake's protection.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch This Is Utah

This Is Utah is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

This is Utah

Liz Adeola travels across the state discovering new and unique experiences, landmarks, cultures, and people. We are traveling around the state to tell YOUR stories. Who knows, we might be in your community next!Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(Gentle Music) Welcome to This is Utah.

I'm your host, Liz Adeola.

Utah is home to what many call the greatest snow on earth, thanks in part to the topic we're diving into on this show.

Take a trip underwater with us as we explore the world of brine shrimp to get a deeper understanding of their impact beyond the Great Salt Lake.

Plus, meet a poet whose powerful words go beyond the page to protect the lake and learn how research and education play a key role in connecting it all for future generations.

This is Utah is made possible in part by the Willard L. Eccles Foundation, the Lawrence T and Janet T. Dee Foundation, and by the contributions to PBS Utah from viewers like you.

Thank you.

(Upbeat Music) - [Liz Adeola] You may not think of the Great Salt Lake as a fine dining destination, but it's just that, for nearly 10 million birds a year.

What keeps them coming back?

Mm-mmm, brine shrimp.

The salt-loving crustaceans that also fuel a multi-million dollar industry.

(boat engine revving) (gentle music) - [Kyle] I feel like I have one of the greatest offices in the world.

I'm a wildlife biologist with the Great Salt Lake Ecosystem Program for the division of wildlife resources for the state of Utah.

And this is where we are once a week, out on the lake trying to collect different samples, in some capacity whether it's doing brine shrimp samples, like this today.

We're doing bird surveys in the spring, in the fall.

The Great Salt Lake Ecosystem Program was developed in the mid 90s, mostly to regulate the commercial harvest of brine shrimp.

But we now incorporate looking at the migratory birds that use the lake.

- It's not just one lake, we focus on five separate bodies of water because we have the North Arm, which is at 30% salinity or saturation.

That's that pink water.

And we have the South Arm of Great Salt Lake which typically sits around 15% on average.

- [Kyle] Great Salt Lake is one large complex of wetland systems, diked pounded wetlands.

Then the outside the dike wetland systems that lead into the freshwater bays of the Lake.

Farmington Bay, Ogden Bay, Bear River Bay.

That then feed into the Saltwater Bays, Gilbert Bay and then the Hypersaline North Arm, Gunnison Bay.

- [Ashley] Nothing other than millions of species of bacteria and archaic live in the North Arm.

And then we have the South Arm here which is home to our brine shrimp, and brine flies.

- [Kyle] Here at Great Salt Lake we have Artemia Franciscana That's the same brine shrimp that occurred in the Pacific Ocean.

- The interesting thing about the species of brine shrimp that is on Great Salt Lake, is they can give live birth to Nauplii, which are baby shrimp.

They can lay eggs, which hatch in 1 to 3 days, or they can lay cysts, which are eggs, but surrounded by a thick chorion shell, that helps protect them from drought, getting exposed on the beach or freezing winter temperatures, and then they can later hatch out.

(boat engine revving) I didn't know about this, until I had this job actually, and I think a lot of people don't realize that there's a multimillion dollar commercial fishery on Great Salt Lake.

It happens every year from October to January.

- So the brine shrimp that are native to Great Salt Lake are unique in that they create a cyst, a dormant egg that can survive really harsh conditions.

That's their target product.

Because you can process it, dry it out, put it in cans, ship it around the world and that's used in the Aquaculture industry.

- For some reason that we still don't know.

The cysts will float at certain times certain conditions, they'll float, and it produces like, an oil slick on the surface of the water, just like an oil slick.

We deploy a, like, a spill containment boom.

And there's two boats and you're moving very, very slowly because the egg doesn't want to be caught.

It wants to go under, it wants to get away from you.

So you have to be very, very careful about that.

Sometimes the boom will take hours, hours to do it.

when we close the boom and cinch it up so that the egg is thick and it's not going anywhere then the big boat pulls up and with hydraulic pumps you pump that into big drainable bags and the water drains out and you're left with the egg.

When that boat goes back to the marina, then we crane them off onto the truck that goes back to the plant.

That's usually the way the harvest goes.

- They're regulated to the point where they're allowed to take the harvestable excess.

So we need 21 cysts per liter left over in the spring to restart the population of brine shrimp because all the brine adults usually die over the winter out of the waters.

6,0 With that, regulation of 21 cysts per liter somehow we have to figure out what the cyst concentrations are around this point.

So to do that, we do multiple measures of the abiotic factors.

- I am sending our mysisd probes down in the water, throughout the water, because I'm going to measure again.

The dissolved oxygen, the salinity and the temperature.

And we do that so our shells have a better chance.

(gentle music) - The salinity of the brine is 22.2 - [Ashley] 22.2 - [Kyle] We also do net pulls where we go look at the density and demographics of the brine shrimp in the water.

And we look at the ratio of adults to juveniles, to Nauplii, to cysts.

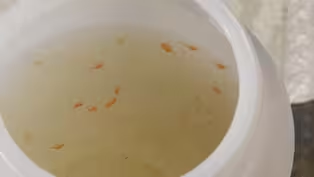

- [Kyle] So we've concentrated that cylinder of water down into about 400mls of water.

And that is our data.

And that'll give us a density of males, females, juveniles, Nauplii, which are the baby shrimp and their cysts (boat engine revving) - The brine shrimp harvest where they ship these brine shrimp eggs all over the world in the aquaculture business is the reason why Great Salt Lake connects us to the world.

If you were to buy farmed shrimp at a grocery store there could be anywhere between a 40 to 50% chance depending on the year, that you're indirectly eating Great Salt Lake brine shrimp, because those shrimp at the store were raised on Great Salt Lake brine shrimp.

- [Kyle] We're also tied to the rest of the world through bird migrations.

So we get anywhere from 4 and a half to 5 million Eared Grebes that come here.

We get anywhere from 10 to 12 million other migratory birds that migrate through the lake, utilize the food resources and then move on through Central and South America.

- I think it's surprising how much life there is in Great Salt Lake.

Just the biomass of shrimp and fly larva in the lake is amazing.

And then the sheer number of birds that we see on this lake is amazing too.

And I feel super lucky to be able to get out on the lake and see it, get out on airboat and see just the hundreds of thousands of different kind of shore birds.

It's always different and that's why I like coming out here.

(Transcendent Guitar Music) - The Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College connects people to the Great Salt Lake using research and education.

- This is one of the largest watersheds in North America.

There are 10 million birds that come to this lake and the bird life is phenomenal.

It is probably a place where I've experienced like this perfect solitude and these birds are all over the water flying overhead and that's the only noise you hear.

It has so many personal holds on me but also professional holds.

I've been so interested in the things that I see and it drives my science.

So I, myself, I think I'm woven into this place.

I can't tell you how many different sorts of interactions I've had with this water and with students and with scientists and with artists and with writers and poets.

And it just brings out the best in everybody and this sense of community, and I love this place.

You think we should try to isolate DNA from those?

- For sure.

- Yeah.

- Yeah, they look good.

- My first entree into lake research was really about how extreme life survives on this planet in an environment that is high sunlight, but they somehow don't get mutations like we do or how they could live in high salt but their cells don't shrivel up like ours would.

I wanted to understand how they do life and think about how that might tell us more about life on other planets.

It's funny how they're not very, that one's green.

And what happened is nobody had done the foundational work on the microorganisms at this lake.

And I think feeling that void of knowledge was really what drove me to start Great Salt Lake Institute.

A hub for everything Great Salt Lake.

We really like to think of ourselves as interdisciplinary, collaborative, synergistic, anything we can do to get more attention on the lake.

And so you see those kind of brown streaks?

- Yes.

- Those are brine fly pupal casings when the brine flies were doing well.

And so today we are working with a team studying the astrobiology of Great Salt Lake.

- This is a great place to study because Mars used to be a watery world, and then as the water evaporated, you had it becoming more and more salty formation of evaporate crystals.

And so by studying the ecosystem here, we get an idea of what might have happened on Mars as it lost its water.

- Since the time that we have been recording history in written documents no one has ever seen the lake this low.

This system is so deficient in water, the groundwater underneath that we're not restoring it when we have a good water year.

So we're in this mega drought and we are experiencing warmer temperatures.

We've done, been diverting water here in the valley for about a century.

That has not set us up to be able to handle the climate conditions we're experiencing right now.

We're really set up for failure and not set up for success.

This is really shocking.

Just like a week ago, this was water.

Two things are going on that there's the shrinking of the lake, so the exposure of the foundation of the system right here.

That's one thing that's happening but then the water becomes too salty for life to handle it.

So that's the second thing that's happening.

So the South Arm is shrinking and it's getting saltier and saltier and saltier.

Right now it's at 19%.

It should be like between 12 and 15.

So the brine shrimp and the brine fly they like to be between 12 and 15, that's a happy place.

The brine flies are dying in multitudes right now, and the brine shrimp the ecological models say they can only really be this productive for about two years before this high salinity starts to impact their reproduction.

So we might see less brine shrimp in the lake.

The birds that eat the flies have nothing to eat and the birds that eat the shrimp, they're gonna start finding them smaller and less nutritious.

So we're standing on microbialite structures right now.

I've been studying these microbialites and the microbes that make them for the last decade or so and I'm really interested in them but also very sad about the state of affairs with them.

So microbialite is literally a rock made by microbes and so they're kind of the bottom of the ecosystem and brine flies and brine shrimp can eat these things and then they feed the birds.

So they're really, really important.

And the ones on the bottom of this lake could be thousands of years old.

These structures have been growing and feeding this ecosystem.

It's just been thriving like this for 13,000 years so it's kind of hard to see it struggling right now.

- So the idea here was to watch a water evaporate.

- My research students are working on, I think one of the most critical problems in the lake right now.

And it is asking a question about resiliency.

- But in the middle we have like some green.

- Yeah, I see.

- Yeah.

- What if the lake is low for a couple years and these microbialites are exposed to air and they dry out and they die?

Do these microbes have the ability to go into some kind of dormancy in a way that in a couple years if we could bring the volume back up of the lake, would they resuscitate and start coming back to life?

They are holding up and this makes me hopeful that they can handle drying up.

- It feels so rewarding when things go right when you see the microbialites in your own lab in a simple model grow and recover and rebound.

It shows that there is some resilience.

If the lake gets more water, we might see a recovery.

- We're totally at a tipping point.

We're like standing on a precipice right now.

Now is the time to shout from the mountaintop that we need water in this lake.

And I go to meetings with the state agency scientists who are working so hard on understanding the system and pulling together all of the best people and the best ideas, I get hopeful.

When you spend your life with young people, it's really important to keep that optimism.

And they keep me optimistic.

They keep me on my toes because they care and they wanna do good work in the world.

That just keeps you driving forward.

- On a windy day like today, you'll spot plenty of ripples in the water here at the Great Salt Lake.

Those small waves can often be used as a metaphor for how people spend their lives trying to make a difference in this world.

One poet is using words to do just that, aiming her pin at rivers in hopes of saving Utah's treasure.

- [Nan] Who is the lake to you?

Among other possibilities, this lake is a great protector.

For over a century and a half, the sailing waters have saved us from ourselves by blanketing toxic heavy metals dumped into our watershed.

Even now, what is left of her body lies between us and a perpetual dust storm.

If we stop choking off her life force, she would continue to protect us from our poisons.

Go to the lake or imagine yourself at the shoreline.

Pause at the water's edge long enough to listen.

Consider her vast and vibrant life.

You too will be able to sense the dynamic intelligence of a life born before recorded time.

We feel like we're at this tipping point where we're about to lose the lake.

That is true.

We may also be at another tipping point where we're about to genuinely fall in love in a way that is visible to each other.

Welcome!

Thanks for coming.

I really appreciate you being here.

It's so awesome.

We're in a lake bed made by the Great Salt Lake anciently.

In very direct relationship with the lake, is the Jordan River is flowing directly into the lake.

I'm a lake facing poet and I am a facilitator of a writing practice called river writing.

I'm on river banks and receding shorelines all the time, inviting people to write and just express their relationship basically to water, to the lake.

This is something sometimes I say before we do slow walking.

Enjoy your life.

(sound bowl reverberating) River writing is a community-based, generative writing practice.

It's also a listening practice and it's a way to be together in creativity rather than isolated working on your own.

I often say that it's like the opposite of the idea where an artist goes into the garret.

Nobody knows, you know, what they're doing and they're painting and they come out with a masterpiece.

River writing is the opposite in that way, like together in the mess.

You might recognize your own words in this.

This river is the track of a tear.

This river is a singer, songwriter.

Ah, this river, how wise you are.

This circle is a bed of compassion.

We know in our hearts that life warrants our reverence, our respect, our humility, and the life of a water body not less than the life of a human body.

Poetry and word choice makes a visible.

♪ The river is flowing.

Human's weren't always this disconnected.

We once knew, so we just need reminding.

About a year ago, I listened to the RadioWest story, the first one of the series that's now running.

Dr. Bonnie Baxter, explaining this current peril of the lake.

- [Dr. Bonnie] Having those scientific numbers basing this on keystone species that if these don't exist, the lake will collapse as an ecosystem.

- [Interviewer] How close are we to the tipping point?

- [Dr. Bonnie] It's possible that we reach that tipping point by November of this year.

Yes.

It's terrifying.

- [Interviewer] Really?

- [Dr. Bonnie] Yes.

We're about two feet in lake elevation from reaching a point where the foundation of this ecosystem will be decimated.

- It was like quite a shock.

The dire situation that we're in was news to me.

I started writing obsessively really.

I think that led to dreaming about the lake.

I would get parts of poems, and that led to beginning the poem, "Irreplaceable".

This idea of collecting enough lines to reflect the square mile area of the lake.

Started out with the ambition to collect 1,700 lines, that's the conservative size of a restored lake.

Now the lake is under 1,000, maybe under 900 square miles.

Because I thought I would have to write a lot of the lines myself, it turns out over 400 people participated in that poem.

It's now over 2,500 lines.

- I love that.

- Thank you so much for coming.

Welcome.

It's amazing we're all here together.

How beautiful.

When praise began to flow, we watched the water rise along both sides of the causeway.

- A very salty lifeless lake, not much for pioneers to harvest but a point of wonder for restless travelers.

- Imagine your ankles covered in water, she said, as we approached the emptiness where the lake should be.

A prayer for restoration, a belief in her bright future.

- We were a great lake, dreaming herself whole again.

Once you had everything, once we had everything.

Art is really the only frequency I know of that will grow our empathy that could change culture.

And the really good news is we're all artists at heart.

We're born to sing.

We're born to write.

We're born to be in relationship in these ways, in ritual.

We need to repair the breech between humans and the rest of the world.

It's one of two futures.

It's a restoration where humans really meet this emergency with the the size of measures that it would take.

So it's not like half measures, it's not polite.

And we could have this beautiful restoration that could still happen.

But that window is closing.

It's closing really fast and we have to look at the other possibility too.

And the lake really has given me poems to express both futures.

When praise began to flow, 11 islands recovered their autonomy microbialites sighed with relief.

When praise began to flow, the dust subsided, metals resettled on the sea floor, arsenic and mercury were lulled back to sleep, blanketed once more by the great weight of water.

The lake is crying, "I thirst".

We must respond with water.

Restoration and repair will be led by ordinary brokenhearted people who are paying attention, by me and by you.

Let us turn our hearts and faces toward the lake and do everything we can do.

Okay, those stories were fascinating, but I know you've got many more.

This is Utah is on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram.

And we'd love for you to share your stories from the Great Salt Lake.

Until next time, I'm Liz Adeola and This is Utah.

This is Utah is made possible in part by the Willard L. Eccles Foundation, the Lawrence T and Janet T. Dee Foundation, and by the contributions to PBS Utah from viewers like you.

Thank you.

(Upbeat Music)

Preview: S4 Ep6 | 29s | Delve into the captivating tale of the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere. (29s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S4 Ep6 | 7m 44s | One woman is taking a stand for the restoration of the Great Salt Lake through her poetry. (7m 44s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S4 Ep6 | 7m 13s | Learn about the brine shrimp of the Great Salt Lake and the threats these creatures face. (7m 13s)

Tipping Point – The Great Salt Lake Institute

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S4 Ep6 | 8m 34s | Great Salt Lake’s ecosystem is in danger, but these scientists are working to save it. (8m 34s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

This Is Utah is a local public television program presented by PBS Utah

Funding for This Is Utah is provided by the Willard L. Eccles Foundation and the Lawrence T. & Janet T. Dee Foundation, and the contributing members of PBS Utah.